Observations on the Memory Layer

Work, when agents do it, requires intelligence, environment, and outcome to exist as a unified whole. The model’s intelligence encounters a structured reality: the emails, documents, user preferences, organizational norms that constitute the environment. The work emerges from their interaction. Memory is what makes this possible.

The model operates under a fundamental constraint: it can only attend to a limited slice of context at any moment. Yet the environment it must engage with (the full reality of what matters for the work) persists far beyond any single attention window. Memory bridges this gap. It reinforces and maintains the presence of objects, ideas, and traces across time, ensuring that what matters remains accessible even as the model’s attention shifts.

Without memory, the environment resets with each interaction. With it, the reality adapts to what the model can process. It selectively persists what enables the work to continue as a coherent activity rather than disconnected episodes.

The core question is: what should systemically persist between interactions, and in what form?

I. The Technical Problem: Memory Substrates and Their Tradeoffs

The Memory Gradient

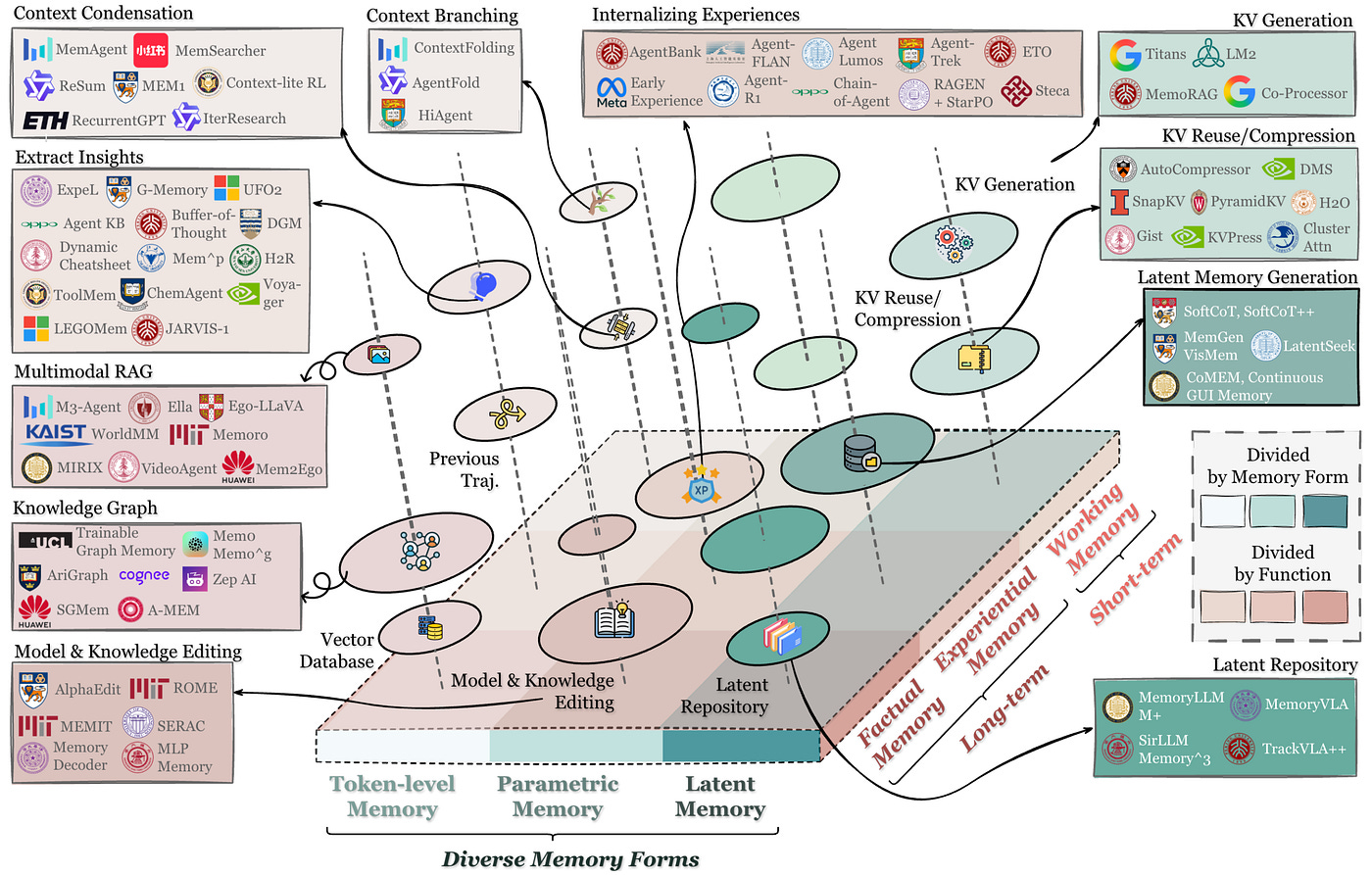

The Hu et al. survey [1] organizes memory along three axes: forms (how it’s represented), functions (what it does for behavior), and dynamics (how it evolves over time). This maps directly to engineering tradeoffs.

Token-level memory is explicit, text-based, and directly inspectable. It’s what most current systems default to because it’s governable. You can see what the agent remembered, attribute decisions to specific evidence, and delete content with confidence.

Experiments have shown that simple filesystem-based approaches can hit 74% accuracy on conversational memory benchmarks using plain file storage, outperforming specialized memory tools [3]. Token-level memory consumes context windows, slows retrieval, and becomes unwieldy at enterprise data volumes. Scale is the main constraint here.

Latent memory lives in the model’s hidden states: the activations that form as it processes context. This is dense, compressed, and computationally efficient. But it’s also opaque. You can’t audit what the model “remembered” or explain why it made a choice. Governance becomes probabilistic.

Skill learning research measures this: agents that learn from experience via in-context demonstrations show 17% improvement over zero-shot performance [4]. The improvement is real, but the mechanism remains interpretable only through behavior, not inspection.

Parametric memory is what fine-tuning and continual learning modify—the weights themselves. This is the densest form, but also the least controllable. One useful pattern is what some practitioners call “core memory” [8]: identity-defining facts that should remain stable even when context changes. Parametric memory can encode this, but at the cost of model governance and the risk of catastrophic forgetting.

A gradient is a good way to look at it because different deployment contexts/timelines need different points on this spectrum.

The Translation Layer: Turning Human Practice to Agentic Memory

The substrates described above define where memory can live, but they don’t explain how organizational knowledge actually gets into those substrates. This is the translation problem, and it’s where most deployments struggle.

Human domain expertise doesn’t arrive in machine-readable form. It exists as:

Tacit knowledge that experts apply without articulating (”I can tell when a customer is about to churn”)

Procedural patterns embedded in how work actually happens (”we always check this before approving that”)

Decision heuristics that evolved through experience (”if X and Y, then escalate to Z”)

Exception-handling logic that never made it into documentation (”when this edge case happens, here’s what we do”)

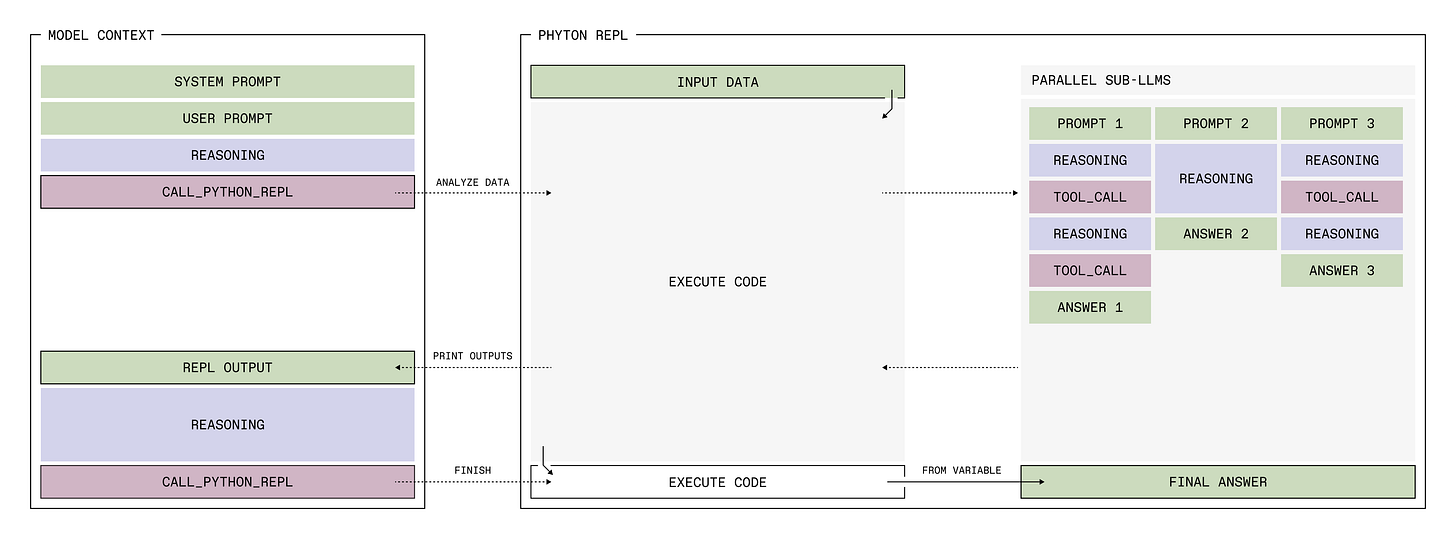

Translating this into memory requires a continuous learning loop. The agent observes work being done, extracts patterns from decision traces, generates candidate skills and heuristics, validates them against human feedback, and integrates validated patterns into its operational memory.

This is not a one-time ingestion process. Work practices evolve. Policies change. Exceptions become standard procedures. The memory layer must update continuously, and that update process must preserve governance properties—you need to know when a pattern was learned, from what evidence, and who validated it.

Research on continual learning in token space [5] shows how agents can update their behaviors over time without catastrophic forgetting, but the real challenge is building the infrastructure that observes human work, extracts the relevant structure, and proposes updates for review. This is where translation tooling becomes critical—not just for bootstrapping memory, but for maintaining it as the organization evolves.

The models that succeed in production won’t just have good retrieval. They’ll have robust mechanisms for translating ongoing human expertise into accumulated agent memory, with clear provenance and governance at every step.

Will Substrates Converge or Stay Separate?

The substrates above—token, latent, parametric—currently require explicit architectural choices. But recent work on Recursive Language Models [14] suggests agents might learn to manage these tradeoffs themselves.

Instead of developers choosing between governable-but-expensive token memory versus efficient-but-opaque latent representations, future agents could learn through reinforcement which representation works for which context. Keep audit trails in tokens. Compress recurring patterns into latent structure. Encode stable knowledge parametrically. The agent learns the boundaries.

This is dynamic self-context-development: rather than passively consuming context until hitting limits, agents actively decide what to retain, compress, delegate to code, or route to fresh sub-instances of themselves. The RLM approach demonstrates this—agents learn what context management strategies improve task outcomes, not hand-coded heuristics.

Scaling attention and context folding are dual approaches to the same problem: what to forget when looking at the past. Better attention architectures delay context rot. Learned context management pushes beyond what attention alone can handle. Both matter. The question is whether the substrates converge into learned strategies, or whether the architectural distinctions persist because governance, scale, and stability pull in different directions.

The Governance Constraint

The choice of memory form determines what governance properties you can enforce. Token-level memory is auditable, attributable, and deletable. You can show regulators exactly what context influenced a decision. You can implement right-to-erasure by removing specific text.

Latent and parametric memory don’t offer these guarantees. They’re black boxes. This matters less in consumer applications where trust is implicit, but it’s a dealbreaker in regulated industries.

Temporal knowledge graph architectures demonstrate one approach to this [6]: representing memory as structured entities with timestamps, relationships, and provenance metadata. This preserves governance properties while enabling semantic retrieval.

The tradeoff is complexity. Building and maintaining knowledge graphs requires infrastructure. It’s overkill for simple chatbots, essential for enterprise deployments where audit trails matter.

The Maintenance Problem

Memory isn’t static. It evolves as the agent operates. Some information becomes stale, contradictory, or irrelevant. How do you manage this?

Bi-temporal models are one answer [6]:

Valid time: When was this fact true in the world?

Transaction time: When did we learn about it?

This lets you handle corrections without losing history. If an agent learns “the CEO is Alice” and later learns “the CEO is now Bob,” both facts persist with proper timestamps. Queries can specify whether they want current state or historical context.

Another approach is automatic summarization and consolidation [5]. As memory accumulates, older interactions get compressed into summaries. Fine details fade, key patterns persist.

The right strategy depends on the application. Legal discovery needs full retention. Customer service probably doesn’t.

II. World Models as Dynamic Composition

When memory substrates accumulate sufficient structure over time—when they capture not just isolated facts but the relationships between entities, the temporal evolution of states, and the patterns of how decisions propagate—something more powerful emerges: a world model of how the organization operates.

Context graphs with sufficient accumulated structure become world models for how the organization operates. Not simulations, but representations of decision dynamics: how exceptions propagate, how escalations work, what happens when configurations change.

A world model isn’t a single storage layer. It’s a dynamic composition of:

Token-level traces capturing decision lineage and audit trails

Latent structures (knowledge graphs, embeddings) enabling efficient retrieval

Parametric capabilities encoding repeated patterns

Working state maintained through active context management

Each substrate contributes different properties. Token-level provides interpretability and governance. Latent enables scale and inference efficiency. Parametric reduces retrieval overhead for stable patterns. Working memory maintains coherence within episodes.

The world model emerges from their interaction, not from any single component. When an agent investigates a production incident, it retrieves similar episodes from the knowledge graph (latent), references runbooks and policies (token-level), applies learned debugging strategies (parametric), and maintains hypothesis state across tool calls (working memory).

This composition is what enables prediction. Given a proposed action, current state, and learned patterns of how the system behaves, the agent can predict outcomes without executing in the real environment.

Transition: This predictive capability has direct market implications. If memory enables richer world models, and world models enable better decisions over time, then memory becomes the substrate where competitive advantage compounds. Organizations that accumulate the right kind of memory—decision traces, not just interaction logs—will develop agents that understand their specific operational reality in ways that generic systems cannot match.

III. Market Structure: Where Do Moats Form?

If memory is what makes agents useful, then memory becomes the place where compounding advantage lives. Gupta & Garg argue that context graphs become a new competitive moat [7]. The core intuition is simple: if one system has lived inside the work long enough to develop a rich, up-to-date representation of what matters, then it will outperform a system that arrives later with a cleaner algorithm but less accumulated structure.

But this market does not resolve into a single “memory database” winner. It resolves into a stack, and the moats form at different layers.

Is “Model-Agnostic” Actually Realistic?

Letta’s framing is that agents that can carry their memories across model generations will outlast any single foundation model [5]. Anthropic’s Agent Skills similarly push toward portability of behavior and tools, with skills published as an open standard [2].

The aspiration is clear: the memory should persist even as the underlying model changes.

The friction is equally clear: memory integration is not substrate-agnostic in the way a SQL database is. Different models:

respond differently to the same retrieved context (format sensitivity is real),

have different tool-calling behaviors and error modes,

reward different cache and summarization strategies,

and benefit from different “context engineering” tactics.

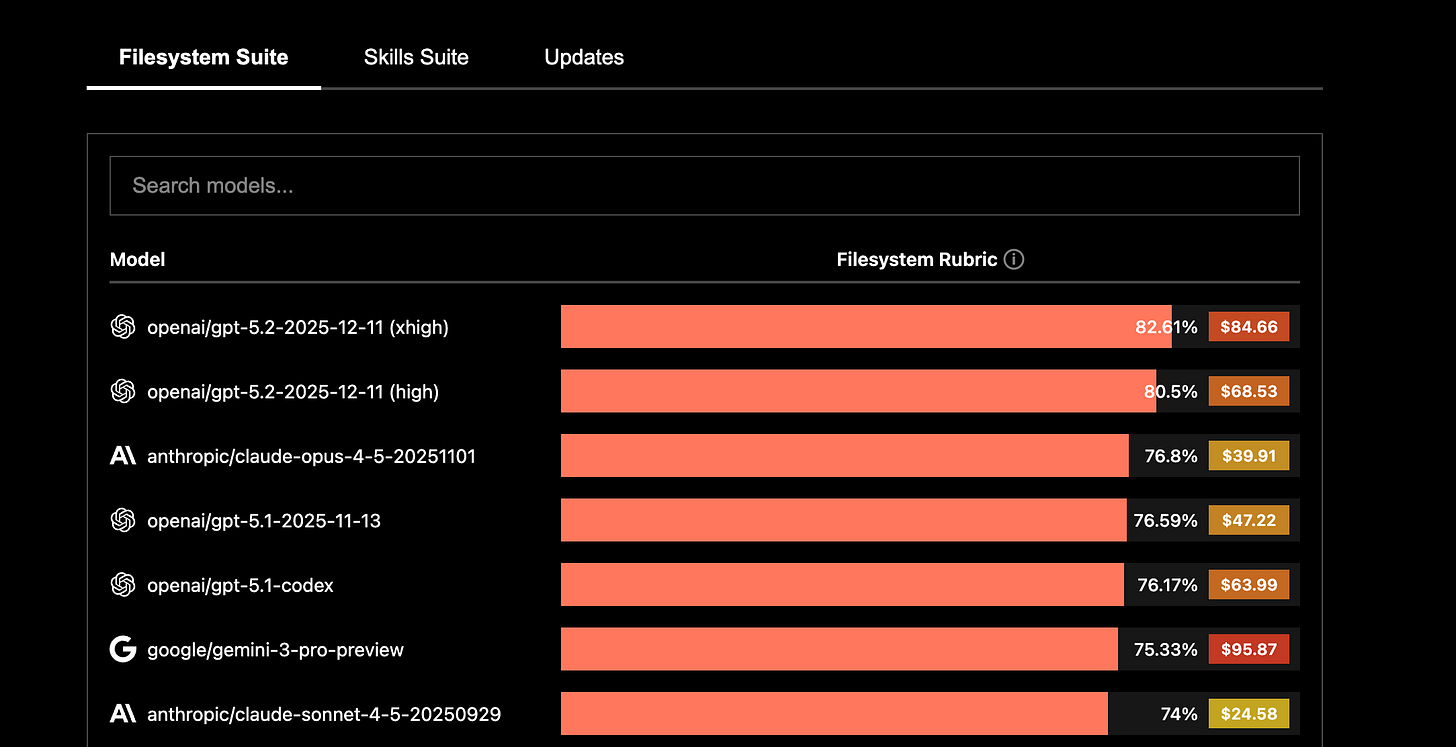

Context-Bench makes this concrete. Letta reports that GPT 5.2 leads Context-Bench at 82.61% while Opus4.5 scores 76.8%, and that the GPT-5.2 run costs more than twice as much in that benchmark, in part because the agent uses more tokens to reach comparable accuracy [10]. This is not a marginal detail. It means that orchestration choices (how you search, what you load, what you summarize, when you stop) are entangled with the model you are driving.

So “model-agnostic” ends up meaning something narrower and more important: the artifacts should be portable (skills, traces, schemas, and memory objects), while the runtime adapts to each model’s quirks.

True model-agnosticism requires an abstraction layer that handles model-specific differences. That layer becomes critical infrastructure. Whoever owns it has leverage. Memory layer companies won’t stay neutral infrastructure. They’ll optimize for specific model families, or they’ll become the orchestration layer that model providers must integrate with.

Consolidation vs. Fragmentation

Two forces pull in opposite directions:

Consolidation forces:

Scale advantages in infrastructure (vector databases, knowledge graphs)

Network effects in skill libraries (more users, more skills, more value)

Model providers bundling memory (OpenAI adding “memory” features [11], Claude adding Skills [2])

Fragmentation forces:

Vertical-specific context is the actual moat (healthcare agents need healthcare memory, legal agents need legal memory)

Governance requirements differ by industry (GDPR, HIPAA, SOC2 all impose different constraints)

Organizational memory is proprietary (your decision traces are your competitive advantage)

Likely outcome: Consolidation at the infrastructure layer (someone wins vector databases, someone wins temporal graphs), fragmentation at the application layer (vertical-specific memory systems with deep domain context).

Do Context Moats Beat Algorithm Moats?

Here’s the strategic question: if Company A has been running agents in your domain for 18 months, accumulating decision traces and learned skills, can Company B catch up with a better retrieval algorithm?

Probably not because value isn’t in retrieval, it’s in what you’ve accumulated. Company A has:

learned which entities matter in your workflows,

built a schema discovered from actual usage patterns,

captured precedents for how exceptions get resolved and who gets pulled in,

and skills that compress repeated tasks into reusable procedures.

These are not just “logs.” They are experiential knowledge baked into the memory layer, and it compounds.

This is also why how you capture memory matters. If you only save interaction transcripts, you end up with a messy archive. If you capture decision traces, what evidence was used, what alternatives were considered, what policy constraints were applied, you end up creating a substrate that can actually support future reasoning and audit.

What Gets Commoditized, What Differentiates

Here’s what I think is

Likely to commoditize

vector databases and basic indexing,

embedding models as generic utilities,

baseline retrieval augmented generation pipelines.

Likely to differentiate

temporal reasoning and bi-temporal memory (because “when” is operationally central) [6],

skill extraction and skill learning pipelines, because they reduce repeated context loading and stabilize behavior over time [4],

governance and audit layers, because enterprises buy control before they buy cleverness.

Likely to remain proprietary

the accumulated organizational context itself: decision traces, precedents, exception-handling pathways, and the evolving schema of how work actually happens.

This suggests a three-layer market structure:

Infrastructure vendors (storage, retrieval primitives) that face low margins and intense competition: Pinecone, Weaviate, Qdrant.

Memory runtime vendors (orchestration, governance, learning, evaluation harnesses) that compete on features and integration quality: Letta/MemGPT, Mem0, Zep, Memobase, MemoryOS. These build the abstraction layers that make memory actually work in production, handling model-specific adaptation, bi-temporal structures, skill extraction, and audit APIs.

Vertical AI platforms (domain-specific agents with proprietary memory) that can support high margins because they capture compounding context: healthcare documentation systems, legal research assistants, engineering tools. Their moat is 18 months of operational traces showing what actually worked.

Where Are the Gaps?

If you assume the above is directionally true, the interesting opportunities are in what is missing, not in what is already overbuilt.

Translation tooling for bootstrapping memory.

Most organizations do not have clean, structured decision traces sitting in a database. They have humans doing work across email, Slack, tickets, documents, spreadsheets, and meetings. Today you either:

manually document everything (which does not scale), or

let agents learn from scratch (which is slow and error-prone).

What is missing are tools that observe human work, extract decision heuristics, generate draft skills and decision traces for review, and continuously update those artifacts as practices evolve. This likely starts as a services-heavy motion, and then gets productized once the patterns stabilize.

Governance-first APIs.

Enterprise memory needs programmatic control over retention, access, deletion, and audit. Token-level memory offers a path to this, but most systems treat governance as an afterthought rather than a design constraint [6]. The missing product category is a memory runtime where permissions, provenance, and auditability are first-class.

Cross-system memory with identity resolution.

Real work happens across systems. If your memory only ingests one source, it is incomplete by construction. The missing platform capability is multi-system ingestion that maintains identity resolution across tools (people, customers, projects, incidents) and can synthesize cross-system context without violating permission boundaries.

This requires solving what amounts to a data unification problem across organizational silos. When a user interacts with your product through email, then Slack, then a support ticket, then a purchase flow, the agent needs to recognize these as the same person pursuing the same goal, not four disconnected interactions. Similarly, when a customer escalation happens, the agent needs to pull together context from CRM records, prior support tickets, product usage logs, and billing history, maintaining proper access controls at every step.

The agents that succeed at real work will be those that can unify this context across different layers and systems [13]. The natural flow of human work doesn’t respect the artificial boundaries between tools. A single intention (”resolve this customer issue”) fragments across dozens of systems, each holding part of the context. Memory systems must bridge these fragments while preserving the governance and permission structures that exist for good reason.

This is technically hard because of data gravity, API limitations, and organizational access controls, but it is necessary for agents that do real work. The winners here won’t just build better connectors, they’ll end up building resolution systems that work across organizational boundaries and synthesize context to get work done in a more governance friendly manner.

Evaluation infrastructure that measures operational outcomes.

Benchmarks like Context-Bench measure an agent’s ability to decide what context to load and how to chain retrieval operations [10]. LongMemEval measures long-term interactive memory abilities such as information extraction, temporal reasoning, and knowledge updates [12].

These are important, but production systems ultimately need evaluation frameworks that measure what organizations care about:

contradiction rates and stale-memory errors,

policy violation rates,

time-to-resolution improvements in real workflows,

auditability under scrutiny.

In other words: production metrics are likely different from the base-level research metrics simply because of the use-case context that necessitates a different scaffolding to make the agent succeed.

Summarizing the principles of persistence

Memory in agentic systems bridges the model’s attentional constraint with the environmental reality required for work. The model can only process a finite slice of context, but the work demands engagement with a much larger operational reality. Memory adapts one to the other.

The technical pov to “what should persist” is: all three substrates need to come-together over time and funtion. Token-level memory provides governance and interpretability. Latent memory enables scale and efficient inference. Parametric memory encodes stable patterns and reduces retrieval overhead. Production systems need all three working together, each contributing what it does best.

The systemic pov is: what persists should compose into world models. Not archives of what happened, but living structure that enables prediction. Representations of how decisions propagate, how exceptions resolve, how the organization actually operates. The substrates work together: token-level traces for provenance, latent structures for retrieval, parametric capabilities for learned behaviors, working memory for coherence.

The market answer is: accumulated operational context becomes proprietary. First-movers who build effective translation layers (converting human expertise into machine-readable decision traces) will have durable advantages. But only if they solve for artifact portability while accepting model-specific orchestration, and only if they build governance in from the start.

Where value accrues becomes clear when you look at the gaps: translation tooling that observes work and extracts structure; governance-first runtimes that treat auditability as foundational; cross-system memory that synthesizes context across organizational boundaries; evaluation frameworks that measure operational outcomes rather than research benchmarks. The question for organizations isn’t “which memory vendor has the best retrieval” but “which approach captures the operational context we’re accumulating—what evidence influenced decisions, what alternatives were considered, what constraints applied—and can we govern, audit, and eventually migrate it?” What matters is accumulation of operational context: real feedback on what worked and what didn’t, decision traces that show reasoning under constraint, patterns extracted from actual practice rather than documentation.

References

[1] Hu et al., “Memory in the Age of AI Agents: A Survey” (Dec 2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.13564

[2] Anthropic, “Equipping agents for the real world with Agent Skills” (2025). https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/equipping-agents-for-the-real-world-with-agent-skills

[3] Letta, “Benchmarking AI Agent Memory” (2025). https://www.letta.com/blog/benchmarking-ai-agent-memory

[4] Letta, “Skill Learning” (2025). https://www.letta.com/blog/skill-learning

[5] Letta, “Continual Learning in Token Space” (Dec 11, 2025). https://www.letta.com/blog/continual-learning

[6] Rasmussen et al., “Zep: A Temporal Knowledge Graph Architecture for Agent Memory” (Jan 2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.13956

[7] Gupta & Garg, “Context Graphs: AI’s Trillion-Dollar Opportunity,” Foundation Capital (2025). https://foundationcapital.com/context-graphs-ais-trillion-dollar-opportunity/

[8] Ronacher, “Agent Design Is Still Hard” (Nov 2025). https://lucumr.pocoo.org/2025/11/21/agents-are-hard/

[9] Ball, “Clouded Judgement: Long Live Systems of Record” (Dec 2025).

[10] Letta, “Context-Bench: Benchmarking LLMs on Agentic Context Engineering” (Oct 30, 2025). https://www.letta.com/blog/context-bench

[11] OpenAI, “Memory and new controls for ChatGPT” (Feb 13, 2024). https://openai.com/index/memory-and-new-controls-for-chatgpt/

[12] Wu et al., “LongMemEval: Benchmarking Chat Assistants on Long-Term Interactive Memory” (Oct 2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.10813

[13] Sasi, “Future of digital identity and interfaces” (Jan 2025). https://nousx.substack.com/p/future-of-digital-identity-and-interfaces

[14] Prime Intellect, “Recursive Language Models: the paradigm of 2026” (Jan 2026). https://www.primeintellect.ai/blog/rlm

Broadly speaking both require you have a sense of what good performance looks like. Then proceed encode some heuristic to - create, change and retrieve context to achieve that good performance. The first two steps can hard-coded in the beginning so you have a intimate sense of how it’s working

For the second, I guess it really depends on the type of data and how you store/index it. What usefulness looks like in that set

Really interesting!! Couple questions:

How do you decide what to pull into the model’s attention when needed?

How do you rank what’s useful and what’s irrelevant?